In A Web Of Dependency

Oftentimes, it is not only the addict who suffers, but also his friends and family.

© W&B/Nina Schneider

‘The next of kin are left behind and overlooked’, says Jens Flassbeck. The psychologist and psychotherapist knows what he is talking about. For decades, he has been working in the blind spot of dependency aid: He cares for the next of kin of addicts.

Their lives are also massively overshadowed by an addictive disorder. And they have their own co-dependent afflictions and problems – sometimes even more and more severe than the addict him- or herself. ‘But the magnitude and explosive force of the next-of-kin set of problems on the one hand and the lack of attention, research and offers of assistance on the other constitute a crass inconsistency’, Flassbeck reckons.

Help for addicts

For addicts, there are streetworkers, addiction counselling and treatment centres, both short and qualified detoxification, out-patient and hospitalised rehabilitation, social rehabilitation, and self-help groups. A pretty divers set of offers. According to data published by German Dependency Aid Statistic (DSHS) last November, there were 315,600 cases of out-patient care and 33,900 cases of hospitalised care in 2020. These were provided by 8,544 out-patient and 135 stationary facilities.

In the words of German Dependency Aid Statistic: ‘Dependency aid in Germany thus belongs to the biggest care systems in the area of addiction in Europe and is characterised by a high qualification and differentiation.’ However, the term ‘co-dependency’ does not appear even once in the 204-page document. The report merely mentions the fact that next of kin and significant others made up eight percent of the 315,600 cases of out-patient care in 2020. In the whole of Germany. As Flassbeck summarises: ‘All support is reserved for the addicts.’

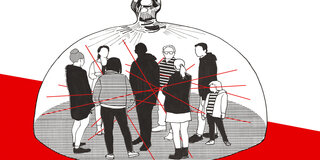

But the second-hand experience of an addictive disorder often has severe and complex consequences. Flassbeck counts depression, anxiety disorder or psychosomatic ailments amongst them. To him it is obvious that an addiction of one person impacts upon others: ‘Dependency is a social system. People suffering from an addictive disorder often act selfishly and irresponsibly. Co-dependent next of kin are often altruistic and excessively responsible-minded.’

They are in effect the antipole. Next of kin try to help the person with an addictive disorder by all means possible. They take responsibility for everything the addict finds impossible to do. ‘The families circle around the addicts and exhaust themselves in the attempt to save them. Subsequently, they lose themselves, don’t look after their needs anymore, and neglect their own aims and interests’, Flassbeck summarises. They become fellow captives of the dependency.

Number of people suffering from co-dependency: unknown

It is hard to say how many people in Germany suffer from co-dependency, because next of kin and significant others are rarely mentioned in the statistics. Research into the subject concurs: ‘The scientific data situation is rather sketchy. There are very few studies and sets of data, and those are mostly concerned with matters of detail like patterns of relationships or the focus upon the [addicted] partner. Although that is quite useful, it does not fully reflect the sincerity and severity of a co-dependency’, Linda Theurich writes in her bachelor thesis submitted at the University of Applied Sciences Zittau / Görlitz and published in 2021.

The mere fact that the search for up-to-date academic texts on the subject leads to a bachelor thesis in Social Work, at the most, is an indication of the lack of research available. We have no data on the case numbers of co-dependency in Germany. The Federal Association of Friendship Circles for Dependency Aid has dared an estimation. Or rather, done some simple arithmetic: the number of people suffering from addictive disorder multiplied by three. That would mean that nine to ten million people in Germany are affected by co-dependency.

One of them is Elke Simons from North Rhine-Westphalia. Her name is invented to protect her anonymity. Her story reveals what one person’s addiction can do to those around him or her. How it takes over their lives, too, and how destructive it can be. ‘My life has run through my hands like sand’, says the 68-year-old today. But she was only able to realise that when her son – then nine years of age – found her unconscious in the bathroom. Nervous breakdown. But first things first.

What addiction can look like

If you ask Simons for her personal history, she initially goes back a long time. ‘I am now of retirement age. I was a well looked-after child of the post-war era and only experienced good times. My parents had been adolescents during the war.’ After the carnage of war, her parents went to university, enjoyed their new freedom and eventually founded a family. Peace, the economic miracle, prosperity. ‘But that did not change the fact that my parents were severely traumatised. My teachers also. In fact all adults.’

So it was a regular occurrence for Simons as a child to find grown-ups towards the end of the night of a wedding, a party, a Saturday with nice weather staring silently into space. Crying. Drunk. ‘Very few of them were alcoholics’, she adds. ‘But even as a child, I learned to understand the language of alcohol, the way it can numb the soul. And that is deeply embedded into our society.’

That is proven by data collected by the German Central Office for Addiction Issues (DHS), published in their annual ‘Addiction Almanac’ (‘Jahrbuch Sucht’). About 1.6 million adults in Germany are addicted to alcohol, followed closely by 1.5 million people addicted to medication. According to the Federal Ministry of Health, about 600,000 people consume illegal drugs like heroin or cannabis up to a problematic level. As for gambling, over 500,000 exhibit a problematic or addictive behaviour.

Elke Simons had to struggle with her husband’s alcohol dependency. Together, they had built their lives: three children, a house, their own business. 1980s prosperity. ‘As time went by, my husband began to drink more and more. So much that he was unable to look after anything anymore. Not our business, not our children’, she remembers. ‘So I tried to manage everything.’ Husband. Addiction. Children. Business. Household.

In the long run, neither her body nor her psyche could cope. But Simons only made changes after she had fainted and her son had to jolt her awake. ‘It was only then that I understood that things could not go on in the same way anymore.’ Soon after, she took her kids, moved house, started a new job qualification and got a divorce. A complete relaunch. During those difficult times, a self-help group gave her the necessary support: an local Al-Anon family group.

Groups that can help

’Alcoholics Anonymous Family Groups’ are the pendant to the ‘Alcoholics Anonymous’ (AA) groups for addicts. Al-Anon is based on the same principle: anonymity and a twelve-steps programme. The programme has its origins in the 1950s. In 2020, the Cochrane Institute – an organisation evaluating the quality of scientific studies – surveyed 27 studies concerned with the AA programme and judged it highly effective – in terms of assuring abstinence.

There a also critical voices, however, about the AA programme and its numerous references to God. ‘The twelve-steps programme is outdated. It is the brainchild of authoritarian times and also religious. It offers a dependent solution to dependent people’, says psychologist Flassbeck. On the other hand, he concedes: ‘Up until today, they are the only self-help movement with its own next-of-kin concept.’ Elke Simons is convinced by that concept. And she still takes part in the meetings. Her ex-husband died in 2006.

Kathrin and Stefan Schmidt have also adopted an invented name for this article. Their daughter became dependant on heroin as a teenager. That was almost twenty years ago. Since then, they have been fellow captives of a particularly perfidious addiction. ‘In the beginning, there was still some hope. But not anymore. You are always worried and never come to rest. Never. Only when she was in prison, as we knew then that she could not do anything in there’, Stefan Schmidt says. He knows, of course, that this may sound heartless to some people. But it is the outcome of years of work for him to speak so candidly about his daughter’s addiction.

‘Addicts have to help themselves‘

Setting boundaries is the key. ‘That is the most important lesson a parent must learn. Because that is the very essence of co-dependency. You think you have to help your child and to give everything you can’, says Kathrin Schmidt. School. Vocational training. Therapies. Doctor’s appointments. Mediation. Police. Court appearances. Organisation. Money. ‘It is your own child, and as a parent you automatically fall into the trap.’

The couple have tried everything to help their daughter. To no avail. And the fight against addiction has left the parents wounded – and those would only heal very slowly. ‘For years, on top of everything, we have blamed ourselves. We have never quite understood why our daughter did that, of all the people. All that was very painful’, says Stefan Schmidt. Besides psychological support and conversations at an addiction counselling centre, their openness about the situation has also helped. They have told friends, acquaintances, even their respective employers. ‘That way, we took away the pressure to conceal something’, Schmidt explains.

And the couple has come to an important realisation: ‘You have to learn that the addicts have to help themselves. I have only understood that in here.’ ‘Here’ is the drug support centre Swabia (‘Drogenhilfe Schwaben’): Knowing how rare decent support structures for co-dependents still are, the support centre has recently founded a self-help group for next of kin and significant others.